Natural capital - market framework: engagement paper

This engagement paper summarises the key natural capital market framework co -development issues and questions that will be explored. The content will be used to help inform, guide and support all participants during the engagement and co-development process.

Section 4: Demand in Natural Capital Markets

This Section describes the nature of demand in natural capital markets. It covers voluntary and mandatory markets; investor motivations; and market development.

Please consider:

- How can the market framework help to increase demand in natural capital markets?

- How should public investment work alongside and enable private investment?

- What market developments are required?

Section summary:

Presently, the voluntary carbon market, facilitated by the Government-backed Woodland Carbon and Peatland Codes, stands as the most developed market in Scotland. It is likely that public funding could be used in a more targeted way to boost private investment in these markets and support increased nature restoration.

Other desirable developments in the voluntary carbon markets include a reliable system of stacking or bundling that enables income to be earned for delivering more than one benefit from the same area of land.

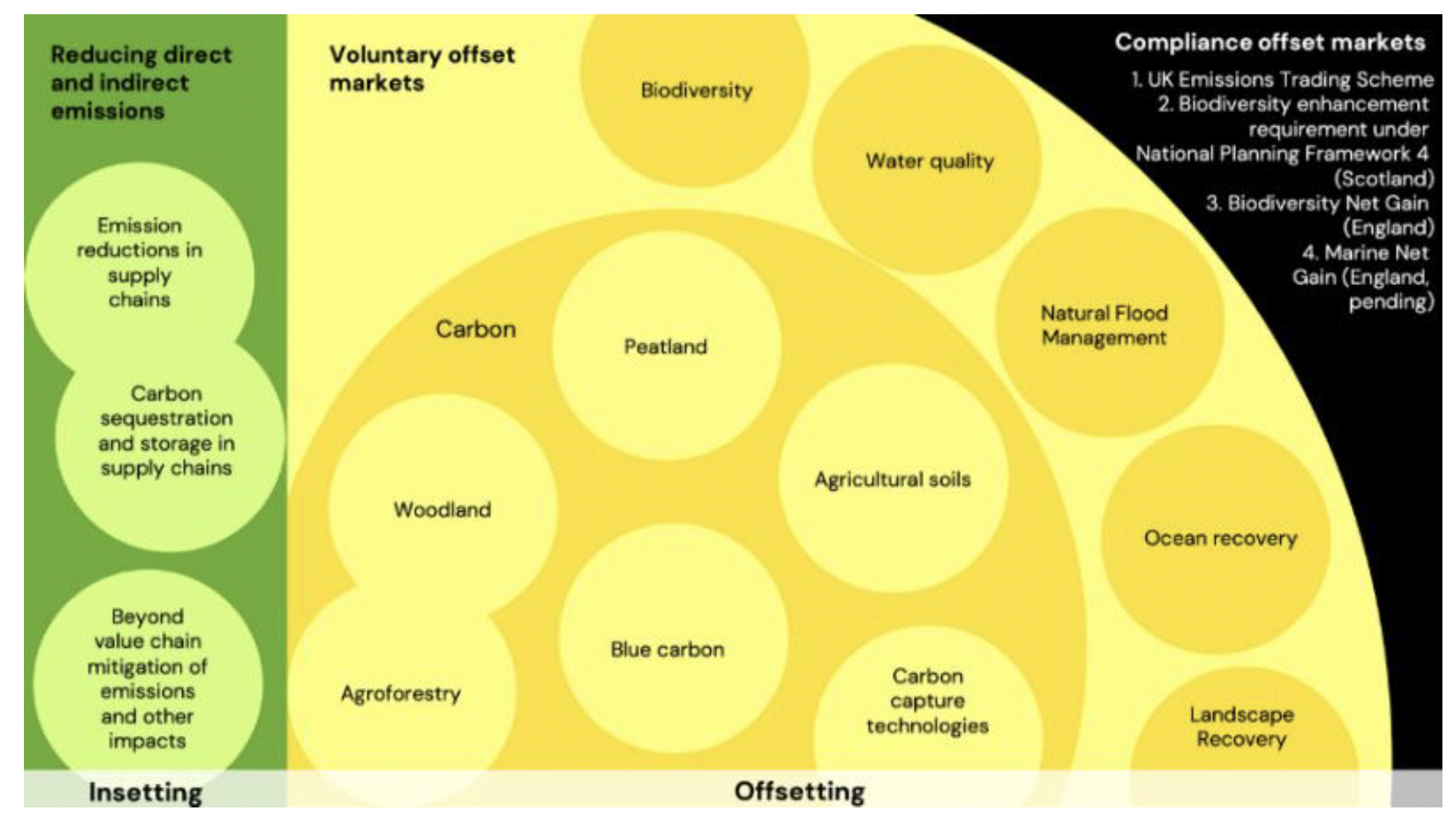

Other less well-developed markets such as biodiversity, water quality, soil, hedgerow and natural flood management will likely benefit from the emergence of new voluntary codes or the creation of compliance markets to generate demand.

Detailed discussion:

1. Market Type

The nature of demand differs by market type. Demand in voluntary markets is different from demand in compliance markets.

Compliance markets

Compliance can be regulated by regional, national or international bodies. In these markets demand is generated by the need for organisations to comply with mandatory regulation.

The UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is the UK’s largest compliance market. It trades finite carbon credits to support the UK 2050 Net Zero target. In 2023 The ETS Authority confirmed its intention to incorporate engineered greenhouse gas removal (GGR) technologies (such as direct air capture and carbon capture and storage) into the UK ETS and to further explore the possibility of including nature-based solutions into the system. This expansion could increase both nature-based and engineered carbon removals, but further work and consultation is needed to ensure integrity and that it supports Scotland’s vision for responsible investment and a just transition.

It is possible to set up compliance markets for other types of natural capital. For instance, in February 2024, Defra implemented Biodiversity Net Gain within the English planning system, mandating developers to buy biodiversity credits for off-site habitat enhancements when on-site restoration proves impractical. Scotland’s planning policies have not sought to establish a mandatory market for biodiversity, opting instead to use its National Planning Framework 4 and Scottish Biodiversity Strategy to safeguard, conserve, restore, and enhance biodiversity.

Voluntary Markets

Voluntary markets are where credits are bought, usually by organisations, for voluntary use rather than to follow legally binding obligations. Private sector actors are primarily motivated to buy these credits to offset their own environmental impact. Initiatives like the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) and the emerging Nature-Related Financial Disclosure (TNFD) aim to stimulate demand in voluntary markets by setting up frameworks and expectations for multinational corporations with large annual turnovers to disclose their climate and nature impacts.

Carbon sequestration is Scotland’s largest voluntary market. Carbon credits, standing for a unit of sequestered carbon dioxide, are sold to and retired by a buyer looking to enhance their climate credentials. At present, these credits are generated through the enhancement of woodland and peatland habitats and are verified by the UK’s high integrity Peatland Code and Woodland Carbon Codes. It’s likely voluntary markets will continue to expand to cover other ecosystems (for example marine, saltmarsh and soil) and other credit types (for example biodiversity credits and water management).

2. What motivates private investment in nature recovery?

Money moves from finance to investment to delivery vehicles (projects, companies) for planned (and measured) outputs and outcomes. Investment has an expectation of a return, by definition. The return has traditionally been financial cash flows. While the types of returns that are acceptable are expanding, the need for some type of financial return will always be there as far as private investment is concerned.

The following is a summary of the key motivations. How important each is would depend on the investor and investment:

- financial cash flows from traditional goods and services;

- compensating harm caused in the past or will be caused in the future through mandatory or voluntary offset or net gain requirements;

- meeting planning conditions with regards to biodiversity, flood risk management and water quality improvements;

- cost savings or risk management for own operations or others;

- investment in developing goods and services for nature recovery. For example, new green technologies;

- peer, consumer, investor, other stakeholder pressures and relevant initiatives like The Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)[13], The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD)[14] and others;

- achieving product differentiation or regulatory standards through investment in nature or industrial design of a consumable product that reduces impacts on nature, green product labelling;

- philanthropy (donations by private individuals) or other reasons to improve wellbeing from the flows of ecosystem services maintained or enhanced without any associated financial cash flow.

3. Future market development

Presently, the voluntary carbon market, facilitated by the Government-backed Woodland Carbon and Peatland Codes, stands as the most developed market in Scotland. Its core offering is the provision of high-integrity carbon offsets. While these codes incorporate provisions to promote co-benefits and integrated land-use decisions, natural capital markets could benefit from further market development.

Code Development

The emergence of new codes such as biodiversity credits, water quality credits, soil codes, hedgerow codes and natural flood management might help to promote diverse and integrated land use and improve a developer’s investable proposition.

The Scottish Government is involved in work to understand the potential for the creation of high-integrity voluntary biodiversity markets. Biodiversity is more challenging than carbon because a unit of biodiversity is more complex to quantify and cost. In a future voluntary market, biodiversity credits could be a mechanism for driving private investment into nature restoration, they could help an organisation measure progress towards becoming nature positive, they would not be considered offsets and could not be tied to biodiversity losses elsewhere.

Stacking

So long as additionality rules are preserved, a robust and high-integrity system of stacking between codes could be a benefit because it will provide another route through which holistic, integrated natural capital projects can be made financially rewarding and viable (See Section 1). For example, stacking is one of the ways woodland creation could be recognised for its carbon, biodiversity and water benefits. Alternatives (or companions) to stacking might be bundling (see below) or regulatory mechanisms that insist on co-benefits (such as the UK forestry Standard).

Bundling

There is also the potential for the emergence of high-integrity codes aimed at providing a more comprehensive valuation of a project's outcomes (also known as bundling). Bundling is when a suite of ecosystem services produced by the same activity is sold at a price premium as a single combined unit in the market (for example the biodiversity and water quality improvement provided by wetland restoration). CivTech’s funding of CreditNature aims to advance this concept.

Case Study: CreditNature

CreditNature aims to develop an option for a new voluntary biodiversity market to help scale responsible private investment into nature restoration in Scotland in a way that aligns with our market vision.

They are currently developing:

1. a framework for measuring ecosystem integrity before and after an intervention.

2. a nature credit – a digital asset certifying a project’s nature positive claim.

4. Project Finance

In November 2023 the Investor Panel made recommendations for mobilising capital to finance Scotland’s transition to Net Zero.[15] Several of these recommendations are relevant to natural capital markets including:

- a preference for projects to be undertaken at scale;

- an upskilling of public sector leaders who engage with investors; and

- a need to maintain a high degree of focus on outputs, as opposed to process.

In response to these recommendations Scottish Government and its agencies have committed to exploring new approaches for attracting the scale of capital required.[16] One area of consideration is ‘blended finance’ mechanisms, where public funding is used in a more targeted way to support nature restoration alongside responsible private investment. There are many different sorts of blended finance mechanisms discussed in the literature. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, some can co-exist. All mechanisms have strengths and weaknesses, and their costs and benefits vary according to a) future market price, b) nature of demand (i.e. voluntary or compliance), and c) the type of market the mechanism is applied to (i.e. peatland, woodland, biodiversity, water etc).

Name |

Description |

|---|---|

Grants |

This is a keyway through which public money is used to enhance Scotland’s natural capital. Current grants include the Forestry Grant Scheme, agriculture support payments, the Peatland Action fund and the Scottish land fund |

Public Land Ownership |

Scotland's public agencies own about 11% of its land mass and continue to consider land acquisitions that can deliver natural capital benefits such as tree planting, peatland restoration and flood alleviation. Investment in these sites is another way public money is put to work enriching Scotland’s natural capital |

Carbon Price Floor Guarantee |

Hypothetically, such a fund would be used to offer the entire market a guaranteed minimum price for carbon |

First Loss Capital Fund |

Hypothetically, such a fund would consist of private money supported by public first loss capital. As returns accrue, such a fund would first pay profits to investors, until it reaches a certain threshold or ‘strike price’, after which the Government would start to receive a return as well |

Project Finance Vehicle |

Hypothetically, this would see a public-private fund provide project developers with finance in the form of a loan or equity injection to support the upfront capital costs |

Liquidity Vehicle |

Hypothetically, such a fund would act as a guaranteed off taker of PIUs, buying credits from projects upfront and holding onto them until they vest into PCUs (Peatland Carbon Units). Projects receive a one-off upfront payment from the sale of PIUs to the fund. Investor returns are generated by the expected increase in value of the credits over time |

Operating Costs Endowment |

Hypothetically, a natural capital project would contribute a certain proportion of their revenues from sales to an endowment. The amount contributed by the projects should be a function of the modelled project lifetime cost. This centralised fund, would then be used to support all projects operating costs |

Individual carbon contracts |

Hypothetically, a government could enter a contract with individual natural capital projects whereby a government agrees to buy a portion of the resulting carbon credits at an agreed price, often above the existing market rate, with guarantees that the project will report against a variety of co-benefits |

Corporate ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) fund |

Hypothetically, such a fund could be administered by public agencies that allows large corporates to donate to restoration costs as part of meeting their ESG/Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) requirements |

5. Next Steps

Especially with regards to meeting important and urgent peatland restoration targets, Scottish Government believes it necessary to explore blended finance approaches. Such an exploration will include:

- achieving a better understanding of the existing private finance market for peatland restoration, emerging actors, and their current approaches;

- deciding what proposed blended finance solutions are practical and appropriate for peatland restoration in Scotland, including undertaking an economic appraisal of these options;

- assessing whether and how to make any blended finance schemes permanent and develop an understanding of how long each potential scheme would take to develop and reach maturity.

Contact

Email: PINC@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback